Filmmaker Gary Sinyor’s irreverent retelling of the Exodus story starts with the baby left floating on the Nile when the Princess takes up Moses, a nicer baby who doesn’t cry and has a proper - er – Moses basket. NotMoses grows up a slave in Prince Moses’ shadow, until God orders both of them to lead the Israelites out of bondage – though it takes feisty Miriam to lead the Exodus. Synor’s intent was Life of Brian meets The Ten Commandments, but it’s rather more Carry On Taking the Tablets, silly humour that sends up the biblical story and religion. Like the Carry On films it could just get the audience vote and become a cult hit.

Filmmaker Gary Sinyor’s irreverent retelling of the Exodus story starts with the baby left floating on the Nile when the Princess takes up Moses, a nicer baby who doesn’t cry and has a proper - er – Moses basket. NotMoses grows up a slave in Prince Moses’ shadow, until God orders both of them to lead the Israelites out of bondage – though it takes feisty Miriam to lead the Exodus. Synor’s intent was Life of Brian meets The Ten Commandments, but it’s rather more Carry On Taking the Tablets, silly humour that sends up the biblical story and religion. Like the Carry On films it could just get the audience vote and become a cult hit.

Knowledge of the Bible and its language (or the first five books anyway) certainly helps, and Synor displays his lightly, learned in cheder (religion school) and synagogue in his Manchester childhood. It all starts with a comedy canter through the stories of the patriarchs leading up to the plight of the Israelites as slaves in Egypt. The Bible lesson turns out to be an extended sermon from Leon Stewart’s well-meaning, though misguided (and anachronistic) rabbi, ministering to the Hebrew slaves. A bit of popular culture helps too as Joseph inevitably bursts into song …

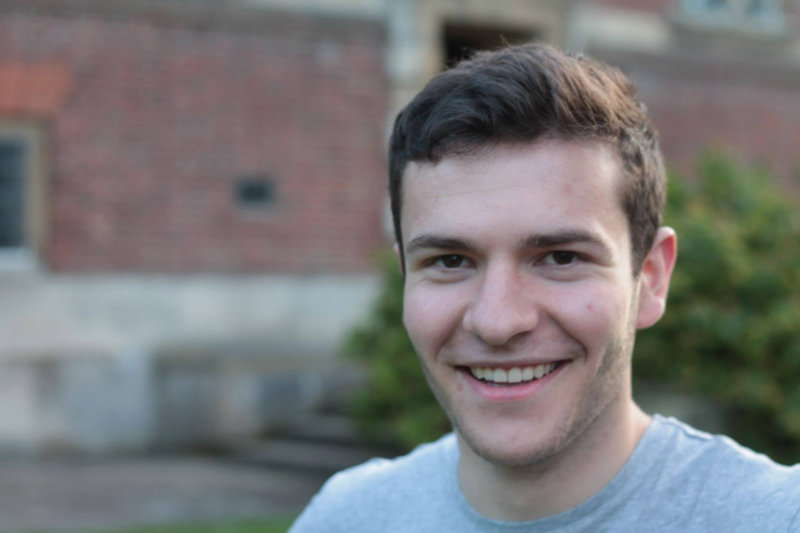

You can’t fault the cast for playing the characters with sincerity as well as a knowing twinkle, for staying in character and not sending it up unless appropriate. Greg Barnett invests NotMoses with the determination and frustration of the atheist who doesn’t believe in God, ready to lead the Children of Israel out of Egypt without anyone’s help. He is comedy paired with Thomas Nelstrop’s Moses, a preppie budding accountant at the palace who grows the beard and perfects the biblical epic lingo once he's heard God in the Burning Bush - and had his kebabs singed there (ooh, Matriarch!).

There’s the expected cast of stock characters, notably the admirable Jasmine Hyde channeling Amanda Barrie in Carry On Cleo, Niv Patel's pouting, petulant Rameses and Joe Morrow as a camp, crowd-pleasing slave driver. But Moses’ sister, Miriam, is a modern fighter for equal women’s rights in this very patriarchal world and Danielle Bird delivers the strongest and most serious speech of the evening with great compassion and conviction.

Life at number 613 (the number of commandments Jews are supposed to keep - geddit), where NotMoses lives with his slave parents, provides a send up of Jewish family life with a nod to Fiddler on the Roof, the Papa (Dana Haqjoo doubling as a legless Pharoah, squatting on his throne like a Dr Who villain or Dan Dare’s Mekon) bemoaning his lack of riches and the Mama (Antonia Davies) preoccupied with food and finding a nice Jewish girl for her son.

And struggling with a series of diktats heralded by thunder, the chosen people have spotted that the Divine Being is also preoccupied with food, not to mention clothing. In the light of the laws on keeping kosher and synagogue readings from of the Torah in recent weeks dwelling in detail on what priests should wear, Sinyor has a point. This is a family Being too, who has to deal with his difficult adolescent Child (presumably omnipresent rather than anachronistic), an extra dimension to ponder, voiced by 13-year-old Izzy Lee at this performance.

There are, of course, plenty more anachronisms, word jokes and double-entendres, from Jethro, Moses' future father-in-law, offering meat he says “Is-lamb” to the toilet humour of the effects of eating unleavened bread (matzah). It often smacks of student revue or something a synagogue youth drama group might come up with for a fundraiser, which does mean there are actually real nuggets of crowd-pleasing fun amongst the groans and lamer jokes.

Synor says the project started life as a film script and this shows in the too frequent fadeouts between the many scenes, effectively salvaged though by Carla Goodman’s sparse sets and Lola Post Production’s epic visual effects creating Egyptian palaces and pyramids and an impressive divided Red Sea, to the soundtrack of Erran Baron Cohen’s matching epic music. The plague of rather realistic plastic frogs which rains down on stage and audience alike is a nice (or should that be nasty) touch.

Some years ago, the playwright Steve Waters wrote that working with a good director is rather like going into analysis – however lucid you might feel to yourself, what emerges in the production of a play exceeds your intention. “Your set might be definitive, your dream cast fixed, but your play in the hands of another often yields a far more surprising piece of theatre than you're capable of envisaging.”

It would have been interesting to see what emerged with a theatre director at the helm and without the expectations of West End opening, albeit in the intimate surroundings of the Arts Theatre, but nevertheless, it certainly gets a lot of laughs so it could prove to be that cult hit.

By Judi Herman

NotMoses runs until 14 May 2016, 7.30pm & 2.30pm, £19.50-£49.50, at Arts Theatre, Great Newport St, WC2H 7JB, 020 7836 8463. https://artstheatrewestend.co.uk